Jewish and Black

In getting at the truth of her own complex heritage, filmmaker Lacey Schwartz captures the ethos of a generation juggling multiple identities.

by Rahel Musleah

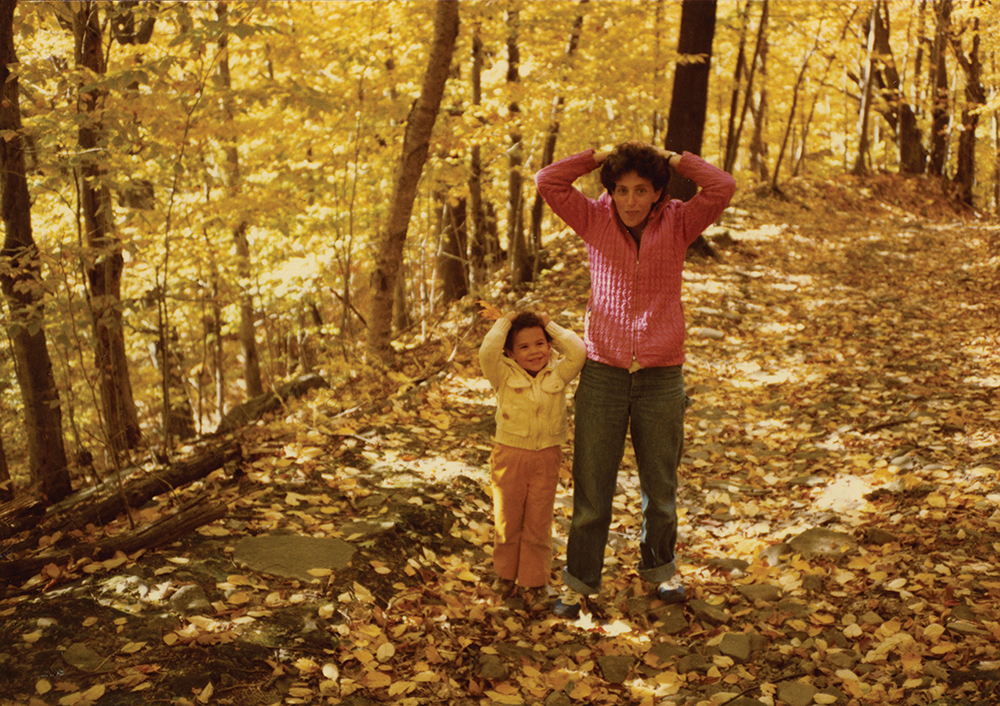

Lacey Schwartz and her mother Peggy in a still from the documentary film Little White Lie.

Lacey Schwartz grew up in Woodstock, N.Y., comfortable in the suburban world of bar mitzvahs and Hebrew school. Despite her light brown skin and tight curls, she believed she was the daughter of two white Jewish parents. Her appearance, they explained, was the legacy of her swarthy Sicilian great-grandfather.

It was not until she was 18 that she pressed her mother for the truth, and found out that her biological father was black—a family friend with whom her mother had had an affair. The revelation changed her life. Today, the 38-year-old Harvard law school graduate and resident of Montclair, N.J., identifies as black or biracial, as well as Jewish. “I never really struggled with being Jewish,” she says, “but how I can be Jewish AND….”

Schwartz unveils the devastating impact of her family’s secrets as she wrestles with identity and race in Little White Lie, a coming-of-age documentary she wrote, produced and narrates. It traveled the film festival circuit and aired in spring 2015 on PBS’s Independent Lens. Though her story is highly personal – sometimes agonizingly so – it reflects the ethos of a contemporary generation juggling multiple identities.

“It’s important to be able to talk about differences in an age where identity politics is increasingly complex,” says Diane Tobin, founder and chief executive of Bechol Lashon (In Every Tongue), an organization that promotes Jewish diversity. Schwartz is national outreach and New York regional director for the organization, which provided funding and served as the film’s executive producer. According to Bechol Lashon’s research, 10 percent of American Jews identify as nonwhite, Asian, Latino or mixed-race, and another 10 percent as Sephardic/Mizrahi. Intermarriage has also increased the number of mixed identities. “Lacey’s story is more complex than many but it’s a way for people to talk about their histories,” says Tobin.

Tobin is particularly moved by Schwartz’s courage in exposing her vulnerability. Indeed, the camera follows Schwartz to tearful therapy sessions, to confrontations with her parents, Peggy and Robert, to frank discussions with family and friends, even to the funeral of her biological father, Rodney. “I wanted people to be having these conversations [about identity], but I wasn’t even talking about it in my own life,” Schwartz explains. “I felt strongly that I couldn’t talk the talk unless I walked the walk.”

Stay up to date with JWI’s work to end violence against women and girls.

The film, which took her eight years to complete, opens with her wedding day preparations. “For a long time I didn’t want to get married,” she intones. “I couldn’t create a new family until I came to terms with what had happened to my own.” Family photos and videos show her parents’ wedding and Schwartz dancing the hora in a white dress at her bat mitzvah. “I wasn’t passing,” she says. “I truly believed I was white. My family knew who they were and they defined who I was.”

Yet, she sensed something was amiss. A synagogue member told her it was nice to have an Ethiopian Jew in their midst. Schwartz confided in her diary that if she could change one thing about herself she would have lighter skin. Her parents never said anything beyond the one comment about her great-grandfather. But the question of race became more difficult to ignore when she entered Kingston High School, which was more diverse. “Black girls would stop me in the hallway and say, `What are you?’ I’d say I was white.”

“I truly believed I was white. My family knew who they were and they defined who I was.”

Her acceptance to Georgetown University shook the truth loose. Based on her photograph, she was admitted as a black person. “That gave me permission to be myself,” she says. She joined the black student alliance. “One drop of black blood and you are black,” she comments. “For the first time in my life I felt I belonged.”

Afraid of losing the world she had grown up in, she kept her white and black worlds segregated but continued to explore. She didn’t know what to do with the part of herself that was white and in the film repeatedly asks friends and relatives how she could have passed for white. “We saw what we wanted to see,” she concludes.

The film is also a portrait of her parents, whose marriage had unraveled when she was a teenager. Her father’s anguish takes the form of dismissiveness; her mother is willing, supportive and honest, open to making amends despite her initial fear. In a visit to the playground she supervised when she was 21 and where she met Rodney, Peggy Schwartz explains, “Before I was your mom, I was me.”

Though Schwartz could not heal her parents, she says she has found peace herself. “I believe in the power of the process. You have to be willing to engage in the process of reconciling even if it’s not easy. I started with a fair amount of anxiety and now I don’t have that anymore.” She encourages others to reveal their stories and have productive conversations about them. A companion website to the film offers a safe place to share them.

“Families are the building blocks of society, so how can we make larger social change if even families aren’t able to talk about these issues?” she asks. See your kids clearly for who they are, she suggests to parents. “Give them confidence and a positive self-image but don’t try to shelter them, ignore the differences or sugar-coat the negative things.” Schwartz hopes the film will catalyze discussion about the consequences of keeping family secrets. “This is a project about the power of telling the truth.”

Her own children, 15-month-old twins, are still too young for conversation. “They don’t even talk yet!” she laughs. In 2011 Schwartz married Antonio Delgado, a black classmate she met at Harvard. A Baptist minister – a close friend of the Delgado family – officiated, but the couple included Jewish rituals like breaking the glass. “The wedding was universalist,” she explains, adding that her husband is not religious. “We wanted to have two officiants – someone from my husband’s life and someone from mine – but the rabbi of the synagogue I grew up in would not officiate.”

In the wake of renewed conversations about race, the film’s release seems both timely and fortuitous. But, says Schwartz, many moments in the past decade would also have been perfect. “Now is a great time, but unfortunately it’s always a great time in this country. More than anything we have to have more real nuanced conversations and awareness of race, not just racism.” Racism is still a critical issue, she says, but the problem doesn’t just exist when a situation of racism arises; it goes deeper. “In the town of Woodstock racism isn’t really an issue. It’s a white liberal community that is blissfully ignorant of it, so we didn’t deal with it at all.”

Her first two films, made at Harvard, also focused on race: Schvartze, a short autobiographical film, and Legally Black, Brown, Yellow and Red, a feature-length documentary on minority experiences at the law school. She worked in corporate, civil rights and entertainment law at several organizations including the American Civil Liberties Union before embarking on her career in television and film production. She is co-founder and CEO of Truth Aid, which produces films and does educational outreach on social issues.

She was motivated to tackle her own questions about identity through her work with Bechol Lashon and Reboot, a collective of Jewish creative professionals who explore meaning, community and identity. “Reboot allowed me the space to think about what it means to be Jewish, why it matters and how I connect to it. It’s been inspirational.” She has received financial support from several Jewish foundations including the Andrea and Charles Bronfman Philanthropies, the Jewish Federations of New York and San Francisco, and the Righteous Persons Foundation.

At Jewish communities throughout the U.S. and on a January tour of Israel, Schwartz has spearheaded discussions and efforts to create spaces for people with multiple identities. “Are young people being asked to leave a piece of themselves at the door or are all parts of their identities being acknowledged?” she asks. Schools and other educational organizations are now using “Passport to Peoplehood,” a curriculum developed for the Bechol Lashon camp.

Schwartz has clearly embraced her own identity. Little White Lie ends as it begins – with her wedding. “I thought about changing my last name,” she says. “As a kid I didn’t like it. Now it seems perfect for me, a clearly Jewish name that literally means `black.’”

(Originally published in spring 2015.)

Rahel Musleah is an award-winning journalist, author and speaker. Visit her website, rahelsjewishindia.com.